Nootka Sound

Early Exploration of Nootka Sound

Editorial courtesy of Nootka Sound Service

by Bernard Cobin, B.A., John Sharpe, B.A. and Lyall Campbell

In 1774 the Spanish became the first Europeans to sight the entrance of Nootka Sound when the Santiago, out of Monterey and under Captain Juan Perez, anchored off Nootka at Estevan Point which he named Punta San Esteban after one of his officers Esteban Jose Martinez. Here he traded with the First Nations people for furs, but made no landing. Because the Spanish did not actually land and then take formal possession, the British would not acknowledge Spanish sovereignty over the area. This exploration oversight would later prove costly to Spain.

On March 29, 1778, in search of the Northwest Passage, Captain James Cook with two  vessels, the Resolution and the Discovery sailed into Nootka Sound looking for a sheltered bay in which to make repairs. As Cook’s ships arrived the Nootka people came out to meet them in canoes: this meeting was the first cultural exchange here between one of the more powerful First Nation’s groups and Europeans. On March 31, Cook anchored in Resolution Cove and while repairs on the ships continued, trading took place between the natives and Cook’s men. The Nootka offered various animal skins for trade, particularly the sea otter, but also offered such goods as carvings, spears and fish hooks. In exchange they wanted knives, chisels, nails, buttons and any kind of metal.

vessels, the Resolution and the Discovery sailed into Nootka Sound looking for a sheltered bay in which to make repairs. As Cook’s ships arrived the Nootka people came out to meet them in canoes: this meeting was the first cultural exchange here between one of the more powerful First Nation’s groups and Europeans. On March 31, Cook anchored in Resolution Cove and while repairs on the ships continued, trading took place between the natives and Cook’s men. The Nootka offered various animal skins for trade, particularly the sea otter, but also offered such goods as carvings, spears and fish hooks. In exchange they wanted knives, chisels, nails, buttons and any kind of metal.

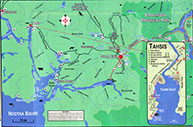

The presence of iron among the Nootkas amazed both Cook and his men and the origin of this iron has never been traced, but may have come about through an overland trade route already established by the Nootka. They used a trail from Tahsis up the Tahsis Valley to Woss Lake, then to the Nimpkish River and to Nimpkish Lake where they traded with east-coast Vancouver Island natives who in turn traded with groups on the Mainland.

Repairs finished, Cook explored the rest of Nootka Sound, stopping at the Nootkan Village of Yuquot where John Webber, his shipboard artist, made water-colours of the sights and peoples. His illustrations provide a fairly accurate picture of both the dwellings and the way of life among the people at that time. After almost a month in Nootka Sound, Cook and his ships left the area laden with furs and a better understanding of the Nootkan people.

Once back in England, news spread of Cook’s expedition and the high prices paid in the Far East for their sea otter pelts. This news particularly excited fur traders and Cook’s maps and observations helped open up the Pacific Coast to further trade and exploration. Unfortunately, Cook didn’t see the results of his findings: he had been killed in the Hawaiian Islands in February, 1779.

In 1785, British Captain James Hanna from China in the Harmon became the first commercial fur trader to arrive in Nootka, the first of hundreds who would make their way to the West Coast as a result of the published accounts of Cook’s voyage. Hanna’s second trip, on the Sea Otter, was not so successful because he had been beaten there by the Captain Cook and the Enterprise which had bought up all the skins. On departing, the owner of the vessels left John Mackay with Maquinna and thus Mackay became the first white resident of British Columbia.

During this period both Spain and Britain sought to expand their colonial possessions and, as a result, Nootka Sound and the North Pacific region became important in the plans of both of them. The Russians also recognized the political value of the area, but the Americans, while seeing political advantages, seemed only interested in its commercial viability.

Many British expeditions, after Cook, arrived to trade with the Nootka. One expedition, commanded by John Meares, arrived in 1786; then in 1788, Mears built a small trading post at Friendly Cove. The Spanish, like the British, realizing the importance of the area, hoping to solidify Spanish sovereignty in it and aware of the movement of Russian explorers down the coast for sea otter pelts and lands to conquer, decided to build a fort at Friendly Cove.

In 1789 Esteban Jose Martinez returned to build that fort. He wasted no time in establishing one at Friendly Cove, but for no known reason abandoned it a few months after arriving. Some months after his departure however, Spain reestablished the fort when, in 1790, Francisco de Eliza, accompanied by three ships, arrived in Nootka and a small Spanish village soon arose on the shores of Friendly Cove. With both the Spanish and the British claiming the area, tensions quickly grew. During Martinez’s brief stay in 1789 he had not only built a fort, but had also seized British ships, stating that the vessels were violating Spanish sovereignty.

These events triggered the Nootka Controversy, which brought the two countries close to war. Spain claimed the territory as a result of the Perez expedition of 1774; and Britain based its claim on Cook’s actual arrival at Nootka in 1778 and on Meares’ purchase of land from Maquinna in 1788. The first Nootka Convention of 1790 partly resolved the impasse. France, Spain’s traditional ally, was involved in the French Revolution and would be of little help, thus Spain returned all seized property and recognized that the West Coast was now open to both Spanish and British traders.

Though war no longer threatened, many unresolved disputes still existed over the territory, in 1792, Britain sent Captain George Vancouver to meet with Bodega y Quadra, the new Spanish commander of Nootka. Though friendly, they could come to no agreement on behalf of their respective countries. Vancouver further ascertained that Spain would not fight for Nootka, and that trade was now the main Spanish focus.

In Paris, in 1793 Britain and Spain signed a second Nootka Convention and trade at Nootka continued to flourish. In 1794 they signed the third and final Nootka Convention. The following year with Spain’s colonial empire in decline, the Spanish dismantled their fort at Nootka, and thus gave the British sovereignty over the area. Soon after the Spanish departure, trade in the area began to decrease because of the drastic decline of the sea otter population, and fewer and fewer ships came to trade.

For twenty years the Nootka people and Friendly Cove had been the center of Pacific Coastal trade. Maquinna had become one of the most powerful and famous of the Northwest Coastal Chiefs and despite European influences the culture of his people had changed very little, although they had come to rely on the goods obtained through the fur trade.

Nevertheless, despite the changes there was no lack of controversy. In 1803 the Boston, under Captain Salter, anchored some three kilometres up the inlet from Friendly Cove and after quarreling with Captain Slater, Maquinna led an assault, and killed all but two of the crew, one of them, a sailmaker named Thompson; the other John Jewitt, a metal worker, who became Maquinna’s slaves for nearly three years, until rescued by Captain Hill of the brig Lydia out of Boston. After being liberated Jewitt published a story about his experiences.

By the early 1800’s, with the decline of that important fur trade, Nootka Sound faded into obscurity. With the sea otters nearly wiped out, even more drastic changes would occur with the coming of permanent settlements on the West Coast. Nevertheless, the profusion of Spanish names on the map of B.C.’s coast will always remind travelers of the coast’s early international history